As an actor there are certain characters that are held sacred. For an actress, heroines like Lady Macbeth, Phaedra, Cordelia, and Hippolyta (the list goes on) are parts considered to be the Mount Everest of acting roles. There is something about these protagonists that seem to be almost unattainable at least not until you are much older, much more skilled. You have to train and win them like they’re Olympic Gold. And even if you get cast in one of these roles and suppose yourself to be ready and credible, panic will (at some point in the rehearsal) inevitably set in: “Am I equipped? Can I actually do the part justice? Will I be able to breathe new life into these juggernauts in a way that the amazing actress before me hasn’t already?” Of course there are going to be days when the answer is, “Yes, of course, I can,” maybe followed by an inaudibly low and defensive voice arguing, “Why couldn’t I?” And then there will be days when you think, “There is no way I can infuse any originality, or newness in to these oh so very famous parts . . . How could I?!” The fact is, these heroines are so well-known in the theatrical cannon that it’s inevitable that people come to see your version with a certain amount of expectation attached; People are familiar with the Judi Dench’s, the Sarah Bernhardt’s and the Nell Gwyn’s who made careers out of playing these famous roles. I think it’s unfortunate that we actresses sometimes feel that because these parts are so famous and possibly overdone, we shouldn’t even make an attempt. Of course it doesn’t help that for this reason, so often for an audition; there are specific speeches that are “off limits.” On most graduate MFA programs or Summer-stock auditions the requirements will read, “Please prepare one classical speech, but please NO VIOLA’S RING SPEECH.” Often times we shy-away from these roles or end up waiting thinking, “I am not old enough or ready to play Lady M, and so I’ll wait.” But what if you miss your chance? Imagine my surprise (and terror) when I recently got cast as Juliet in my training program at The Old Vic Theatre School. Before I left New York I had decided that my chances of ever playing Her were slim-to-none; I’m getting older, I’m too cynical no longer youthful enough in spirit. And I accepted my reality that I may never play Juliet outside my apartment, and for anyone other than my Mom, boyfriend, or cat. And NOW I found myself in a room with a group of actors and a director staring down at some highlighted words on page reading, “Romeo Romeo wherefor art thou Romeo . . .” With a rather massive lump in my throat and a tightness in my chest I sat around a circle for a table read and thought . . . “How am I going to do this?”

As an actor there are certain characters that are held sacred. For an actress, heroines like Lady Macbeth, Phaedra, Cordelia, and Hippolyta (the list goes on) are parts considered to be the Mount Everest of acting roles. There is something about these protagonists that seem to be almost unattainable at least not until you are much older, much more skilled. You have to train and win them like they’re Olympic Gold. And even if you get cast in one of these roles and suppose yourself to be ready and credible, panic will (at some point in the rehearsal) inevitably set in: “Am I equipped? Can I actually do the part justice? Will I be able to breathe new life into these juggernauts in a way that the amazing actress before me hasn’t already?” Of course there are going to be days when the answer is, “Yes, of course, I can,” maybe followed by an inaudibly low and defensive voice arguing, “Why couldn’t I?” And then there will be days when you think, “There is no way I can infuse any originality, or newness in to these oh so very famous parts . . . How could I?!” The fact is, these heroines are so well-known in the theatrical cannon that it’s inevitable that people come to see your version with a certain amount of expectation attached; People are familiar with the Judi Dench’s, the Sarah Bernhardt’s and the Nell Gwyn’s who made careers out of playing these famous roles. I think it’s unfortunate that we actresses sometimes feel that because these parts are so famous and possibly overdone, we shouldn’t even make an attempt. Of course it doesn’t help that for this reason, so often for an audition; there are specific speeches that are “off limits.” On most graduate MFA programs or Summer-stock auditions the requirements will read, “Please prepare one classical speech, but please NO VIOLA’S RING SPEECH.” Often times we shy-away from these roles or end up waiting thinking, “I am not old enough or ready to play Lady M, and so I’ll wait.” But what if you miss your chance? Imagine my surprise (and terror) when I recently got cast as Juliet in my training program at The Old Vic Theatre School. Before I left New York I had decided that my chances of ever playing Her were slim-to-none; I’m getting older, I’m too cynical no longer youthful enough in spirit. And I accepted my reality that I may never play Juliet outside my apartment, and for anyone other than my Mom, boyfriend, or cat. And NOW I found myself in a room with a group of actors and a director staring down at some highlighted words on page reading, “Romeo Romeo wherefor art thou Romeo . . .” With a rather massive lump in my throat and a tightness in my chest I sat around a circle for a table read and thought . . . “How am I going to do this?”

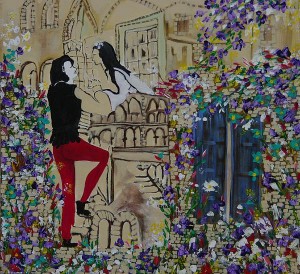

One thing that I really like about the English approach to theatre training is that they don’t put the same sacred stamp on these roles like we seem to do in the states. They train actors to feel that, not only are we entitled to a Go, but it is our duty as actors to strive for the summit as many times and as often as we can. The mentality is: These are great roles, great speeches, and if you want to be a great actress, then you have to work them at any age and skill-level. I came to realize during my rehearsal process that the only way to tackle Juliet is to dive in and get out of a comparative mindset; to take a massive bite out of her and begin to chew (even if I start to choke). You have to focus on one line at a time. Not long into the rehearsal process I had managed to truly convince myself that I was the only person to ever have experienced what Juliet experiences. I went through my script word-by-word and really contemplated the meaning of each thought. I found how each thought leads in to the next one. I found the journey. I personalized it and made it my own. I focused a lot on the magic “What if?” What if Romeo’s love really is honorable? What if we could get our parent’s blessings? What if my letter reaches him on time and he knows my plans? What if we get our happily ever after? When you focus on the “What if,” the playing of it becomes fresh and personal. What seemed sanctified and inaccessible became mine and no one else’s. The feedback I got reflected just that. I was original. I made someone hear the lines for the first time and in a new way. What I learned from this experience is not to put any of these roles in a trophy case behind glass to worship and wait for the day that you’re good enough to take them out. Don’t wait to be good, worthy, or older to play these classic and wonderful parts. Don’t wait to be cast in them either. Play with them on your own. Now certainly if you decide to audition for the MFA program at NYU, you might want to avoid Viola’s ring speech, but don’t let that stop you from working on it on your own. And most importantly don’t fall into a comparative mindset. While at the National Portrait Gallery in London I mused over the exhibit “The First Actresses.” I stared at portraits of Nell Gwyn, Sarah Siddons, Mary Robinson, and Hester Booth in portraitures of their famous portrayals of these roles . . . And after a while I could see no difference between them and me other than the high-hair and corsets.